How Mutually “Unintelligible” are Chechen and Ingush?

One of the first phrases a student of Chechen or Ingush encounters is vai naax (Ingush: vai nax), which translates to our people. Vai nax—we will use the Ingush version—is a term that reflects a fascinating sociolinguistic phenomenon: that Chechen and Ingush are, as Johanna Nichols wrote, “distinct languages and not mutually intelligible, but because of widespread passive bilingualism they form a single speech community.” As a non-native speaker of both Chechen (nuoxchiin mott) and Ingush (ghalghai or vai mott), I have always been particularly interested in mutual intelligibility and the pitfalls of defining it; so I decided to ask a few Ingush friends, now living in the United States, how they practiced this “passive bilingualism” in everyday life.

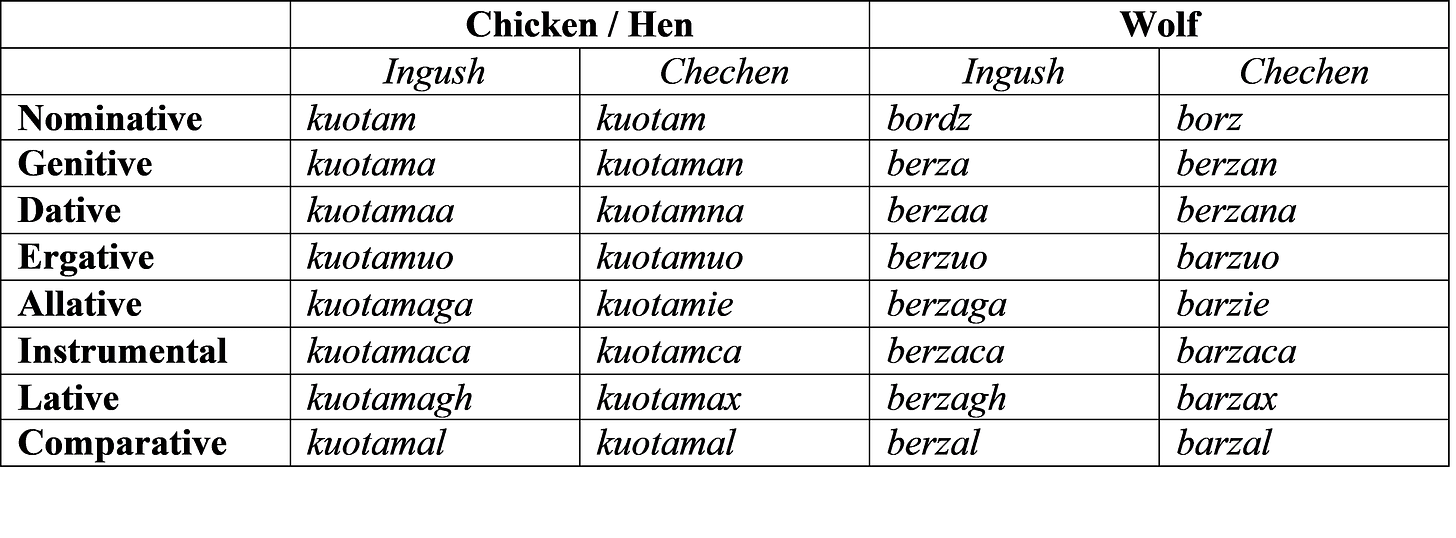

First, though, let’s compare a few nouns, verbs, and phrases in Chechen and Ingush to get a sense of how “close” they really are. Take the case system. You may remember from my last article that the Chechen and Ingush word for chicken is borrowed from Kartvelian—i.e., Chechen / Ingush котам (kuotam) and Georgian ქათამი (katami). Here it is declined, along with wolf.

Very generally, in Chechen and Ingush the nominative, or absolutive case, is the subject of an intransitive verb (a verb that doesn’t take a direct object), or the object of a transitive verb; the genitive usually conveys possession; the dative, indirect objects; the allative a goal or destination; the instrumental, accompaniment; the lative, the source; and the comparative, well, comparison. The ergative case is used when the noun is the subject of a transitive verb. Georgian has an ergative case too, which we described briefly in “What Makes Georgian Verbs So Difficult?”

As you can see, while the case endings differ, it’s evident that Chechen and Ingush are closely related. Interestingly, with the word for wolf, Chechen borz and Ingush bordz undergo ablaut—a term for vowel shift. But while Ingush ablaut applies to all cases except the nominative, in Chechen it switches form o to e in the genitive and dative, and o to a in ergative, instrumental, etc.

Ablaut plays an important role in Chechen and Ingush: whether it be declining nouns as seen above, or conjugating verbs. Ablaut, or vowel shift, often indicates a change in verb tense. English is another language that has made extensive use of this, e.g., sing, sang, sung.

Now let’s look at some sentences. Pay attention to how the vowels shift from present to past, and how those shifts differ in each language.

Ingush: Aaz shura mol. Aaz shura maelar.

Chechen: As shura molu. As shura melira.

Gloss: I-ERG milk-NOM drink-PRES. I-ERG milk-NOM drink-WITNESSEDPAST

I drink milk. I drank milk.

Ingush: Wa fy oal? Wa fy ealar?

Chechen: Ahw hun oolu? Ahw hun eelira?

Gloss: You-ERG what say-Pres? You-Erg what say- WITNESSEDPAST

What are you saying? What did you say?

Bearing these examples in mind, I asked one friend—born in Nazran, Ingushetia—how well he understands Chechen.

“We do understand each other,” he replied, but it still depends on where those Chechens are from. “I remember some Chechen guys who lived in a [highland] village, and I couldn’t understand them as well. But then again, Chechens from the city also had a tough time understanding some of their words.”

This brings up the question of dialects, of which Chechen has many. “The central dialect, the one spoken in Grozny,” my Ingush friend added, “I can understand about 80 percent of. If there is something I don’t understand, it’s usually around a specific word, which we can then work around.”

Perhaps the most difficult thing for Ingush speaking Chechen, and Chechens speaking Ingush are learning the different ways vowels shift in their respective languages. Another Ingush friend adds, “I don’t know what the rules are for vowel sounds in Chechen. I’m not sure how the stems change.”

Some words are, of course, completely different. Take, for example, bread: meaq in Ingush and beepag in Chechen. Chechen also has multiple ways to issue a command, many of which soften the tone. For example:

Diesha! Read!

But:

Dieshal! Why don’t you read; dieshahw, please read; dieshalahw, please read.

Thus, Chechens often joke that Ingush sounds a bit commanding!

A few other things can indicate Ingush vs. Chechen right away. The ubiquitous participle d.u agrees with noun class in Chechen. It can often mean “to be.” For example:

Hara ber bu.

This is a child. (ber = child).

Iza lor ju, t’q’a suo lor vu.

She is a doctor, and I am a doctor.

In Ingush the participle is d.y (д.е), and sometimes the same noun falls into different noun classes:

Jer ber dy.

This is a child. (dy not by)

Finally, the sound “f” is not found in Chechen except for loanwords coming from Russian. Hence, the prominent Ingush question word fy or what sounds very out of place to a Chechen ear, and immediately indicates Ingush.

When it comes to language use, one friend told me they feel “Chechens use Chechen far more than we use Ingush. It seems [the local government] has been doing a lot to develop their language: hosting events, printing and publishing, and other activities.” Which leads of course, to questions about how and when Ingush is spoken nowadays. Here, according to a few friends, is a helpful table. I should stress that this is not scientific, simply anecdotal.

According to these friends, a combination of Russian and Ingush is spoken throughout one’s daily life. But what does a mix of two languages really mean? For that we must dig a bit deeper.

Often the topic for which a language is used indicates more than the setting. My friends, for example, use Ingush when they are speaking about casual things—what happened during your day? what’s for dinner tonight? And when one is talking about something specific at work, something to do with science, etc., Russian is more common. Children now use more Russian in their daily speech; the language of study at school, the movies and cartoons they watch, are all in Russian. Some Ingush enthusiasts, however, are working on translating cartoons.

Feelings, according to one friend, sound much better in Ingush than in Russian: Sun xozxet iza (I like him or her) is more “right” than on/ona mne nravitsya.

But even this fails to take into account the nuance of what a “mix” really means. Take for example, this sentence:

“I had a tough day at work today. I went to the store before work, and I arrived late. Everyone was already in a meeting, discussing important sales”

First in Russian:

Сегодня у меня был тяжелый день на работе. Я пошел в магазин перед работой и опоздал. Все уже были в совещании и обсуждали важные продажи.

Cevodnya u menya byl tyazhely den’ na rabote. Ya poshel v magazine pered robotoi i opozdal. Vse uzhe byli v soveschanii i obsuzhdali vazhnye prodazhi.

Now, in Ingush-Russian “mix,” highlighting in bold the words of Russian-origin.

Hal di der sa taxan. Tikat vaxa tew visavar so, tahkh balkh so daquechach berrigazh sovesheni ya baxar, tsha vazhni prodazhash obsuzhdat’ desh.

Clearly, much more is going on here than just switching between two separate and distinct languages. Rather, I would argue, Ingush is incorporating Russian vocabulary, and making it its own. Moreover, these three sentences could be said in a bewildering variety of ways, depending on each speakers’ background and comfort in Ingush and Russian respectively. Many would choose to use more Russian terms.

My friend who uttered the above lines put it best: “I guess there could be three stages of the “mix”: the first is a high mastery of Ingush—these are people who know many genuine Ingush words, I however know very few; second are those who try to speak Ingush, but have to use a lot of Russian in their speech; and third are those who rarely use Ingush.”